23 April 2020

Leadership15 May 2020

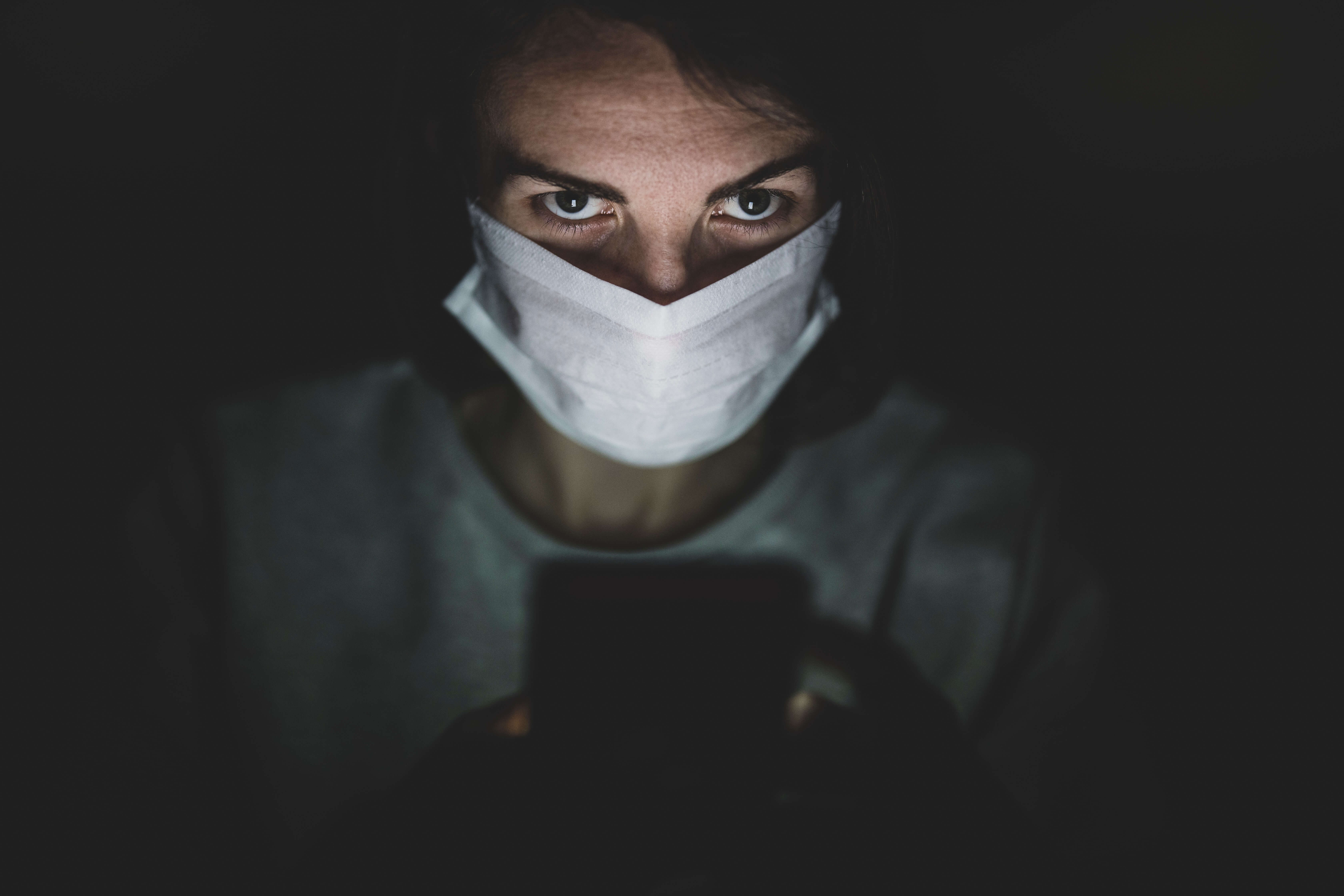

LeadershipStories are the building blocks of our culture and values, but what happens when they take a sinister turn?

Our AU Senior Director Glenn Radford explores why conspiracy theories may have proliferated in recent years, especially amidst the pandemic. He investigates how an increasingly intangible world has eroded trust, why we are innately susceptible to sinister stories and what people empowerment tips businesses can adopt to navigate the dangerous territory of misinformation.

Stories that shape our culture

Worldwide conspiracism has exploded across digital media in recent weeks with sinister and strange allegations about the origins of COVID-19 and government weaponization of 5G.

It is no longer just the ramblings of that well-oiled and misaligned bloke at the pub after midnight; it has infiltrated our communities and personal spheres. You may have recently awoken to notifications on your phone showing your distant cousin’s xenophobic Facebook videos about China’s ‘attempt at world-domination’, or Bill Gates’ ‘plans for depopulation through vaccination’.

Conspiracy theories reject standard accounts of events and instead credit covert groups or organizations, usually of elevated power or status, with carrying out a secret plot. They are often based on irrefutable principles, rather than testable hypotheses.

There is the temptation to dismiss these theorists as an estranged minority, however, nearly 1 in 3 Americans believe COVID-19 was made in a lab, just as 1 in 6 Chinese people believe GMOs were created by the US as a form of “bioterrorism”. This is all despite significant scientific and expert accounts stating otherwise.

Whilst often associated with political events, conspiracies run deep in the corporate world too. Many believe that businesses conspire against us – from the way products are sourced and manufactured, to the information held, used, or sold about us.

So why is this counter-cultural, counter-scientific storytelling potentially bigger than ever?

Our new intangible world

We increasingly live in a world where shared objective standards for truth have been eroded. Politicians and news agencies finger-point until we remember only the finger-pointing. 24-hour news cycles increasingly demand sensationalism or bothsidesism to add artificial narrative to stories. We have seen the propagation of conspicuous possibilities through a long list of occult documentaries on our TV screens, such as Making a Murderer, Citizenfour, The Great Hack and Cowspiracy.

According to Merriam-Webster: "Bothsidesing is a critique leveled at the media for the practice of finding a second angle on a story in an attempt at appearing "fair" to each side, which can often be seen as lending credibility to a side or objectionable idea that has none."

The icing on this indigestible cake is the proliferation of social media and video sharing platforms. During social isolation, digital platforms have given rise to an extreme magnification of minority views. Big tech is now under significant public pressure to deny serial misinformers, fake experts and radicals access to likes, shares, alien emojis and ultimately advertising dollars. High profile de-platforming cases, as with Alex Jones’ InfoWars, have seemingly taught others one thing – it is possible to make thousands of dollars from peddling bull***t online.

The intangible cultural transformation we have experienced is perhaps best summarised through a linguistic lens. ‘Post-truth’ was the Oxford English Dictionary’s Word of the Year in 2016, as was ‘Fake news’ for Collins English Dictionary in 2017, and ‘Misinformation’ was elected by Dictionary.com in 2018. Dictionary.com states “we believe understanding the concept is vital to identifying misinformation in the wild, and ultimately curbing its impact”.

Left unchecked, conspiracy theories can become powerful change agents

The societal and economic impact of conspiracy theories can be far reaching. Would Trump have been able to elevate his political campaign without first plugging the “birther movement” to discredit Obama (and later tenaciously crediting himself for ‘putting the lie to rest’)? Have US livestock interests quashed Burger King’s meat-free burger demand by conspiring that the Impossible Whoppers give men breasts?

Whether you believe these elaborate plots or not, conspiracy theories have the power to cause great confusion for consumers, businesses, and economies. Before we think about how leaders can protect their businesses, we need to understand why humankind is surprisingly susceptible to falling for even the most outlandish claims.

The psychology of conspiracy theories

The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories tells us that our belief in these sinister and implausible stories is to a great extent driven by 3 psychological motives:

- “Epistemic” – our need to understand and explain our environment

- “Existential” – feeling safe and in control

- “Social” – preserving a positive self-image and group identity

These fundamental needs can explain why conspiracy theories might thrive during our current uncertain, stressful, and isolated pandemic lifestyles. Evil puppet masters are easier for us to accept than random chaos. Knowledge helps boost our self-esteem; it makes us feel clever. If we suddenly share our beliefs with other people, we now enjoy a group identity and the social support it affords.

Lessons for business leaders

Given what we know about our needs to understand, control, and preserve our self-esteem, we must avoid scornful reactions, which includes stubbornly attempting to win the argument, or attaining intellectual or moral high ground. If you must address misinformation, strongly consider whether outright denial is the right approach.

Studies investigating rumour denial have shown that businesses simply rejecting allegations can be met with heavy scepticism, as consumers interpret the behaviour as self-serving. The US Italian restaurant chain Olive Garden did not expect their casual denial of a Twitter user’s allegations to be retweeted over 250,000 times and shared with tens of millions of consumers adorned with the hastag #BoycottOliveGarden.

Instead, the more effective approach puts people back in control of their knowledge; simply asking consumers to evaluate whether they can be confident in the rumour, based on the information they have available, is more empowering.

During times of uncertainty, fear and doubt, consumers are more susceptible to the extreme thinking of conspiracy. Leaders and brand ambassadors must work harder to show empathy and transparency, build trust and open-mindedness to new, complex, or unexpected actions. Get to the heart of your audience, the key cultural and social dilemmas that define them, and their triggers of distrust. Engage in social listening and proactively educate consumers to navigate the complexities of your products, services, or brand values and elevate trust to become household names.

Like this article?

If you'd like to hear more, subscribe to Frame or live chat to the team right here on this page. Why not say hi to Glenn on LinkedIn too?

Tags:

Tags: